An infestation of Lonicera japonica (Japanese honeysuckle)

First off, a big thank you to the subscriber who came up to me at the CT Flower & Garden Show in Hartford in February and asked about invasive honeysuckles.

I don’t know how but honeysuckles have somehow escaped being featured as an invasive in Connecticut Gardener. Until now, that is! Very tricky of it.

A whopping six species of Lonicera are considered invasive in Connecticut. Perhaps the best known, Lonicera japonica (Japanese honeysuckle), is a perennial woody vine. The other five are perennial shrubs.

How Do You Tell Them Apart?

There are a number of botanical differences but the easiest one to remember is this … native honeysuckles have solid stems while the invasives all have hollow stems to some degree. Need a mnemonic? How about ‘Natives do you a solid and invasives suck.’

PERENNIAL WOODY VINE

Lonicera japonica (Japanese Honeysuckle)

A climbing or trailing woody vine

(a liana) with reddish-brown stems that originated in Eastern Asia. It was introduced in Long Island in 1806 as an ornamental landscape plant and for use with wildlife and erosion control.

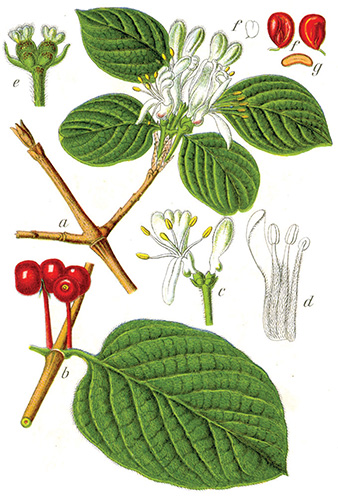

The oppositely arranged ovate leaves are 1-5 inches long and about half as wide. Tubular, fragrant white bi-lobed flowers appear in June and turn yellow as they age.

Unlike native honeysuckles, it has distinctly separate upper leaves and small paired bluish-black berries with a few seeds.

The seeds are spread by wildlife but it also has underground rhizomes and aboveground runners that help it spread locally.

The quick-growing vines twine around the stems and trunks of other plants and can grow to 30 feet or more with support from trees. It forms large tangles that smother other vegetation, resulting in loss of habitat and bio-diversity. It can even kill saplings and shrubs by strangling them (girdling).

BUSH HONEYSUCKLES

WOODY PERENNIAL SHRUBS

Lonicera maackii (Amur Honeysuckle)

It’s native to Asia, including China, Mongolia, Siberia and Korea, and used for erosion control. It comes from the Amur River, in its home range, which borders Manchuria and Siberia.

Arguably the largest of the bush types – with some plants reaching a height of 30 feet. Its growth habit is highly variable depending on conditions.

Elliptical opposite leaves are 2-3 inches long. The leaves are sometimes dark green above and lighter below. Paired, tubular flowers are borne on peduncles from leaf axils in late May or early June. They start out creamy white, sometimes tinged with pink, and yellow as they age.

Quarter-inch red-to-black berries are produced in late summer, ripen in late fall and persist into winter. Birds like the fruit and spread the seeds when they defecate. As with L. japonica, vegetative sprouting helps it spread locally.

It is highly adaptable to light and moisture conditions, and is often found in disturbed areas. It thrives in calcareous soils, such as those found in the cool northwest corner of Connecticut.

It leafs out early and forms dense thickets that are too shady for most natives to survive.

Lonicera morrowii (Morrow’s Honeysuckle)

Originally imported as an ornamental in the 1860s. It has also been planted for wildlife cover and erosion control. Its native range includes Northeast China, Japan and Korea.

It has spread to natural areas but also threatens gardens and parks. It often co-occurs with Amur honeysuckle.

It is shade tolerant but thrives in full sun. It invades forests and forest edges, floodplains, pastures, old fields, roadsides and other disturbed areas.

It’s a multi-stemmed shrub that can grow to 8 feet tall. The elliptical to oblong leaves are 1-3 inches long and hairy on the underside.

Tubular cream-colored flowers appear from May to June and turn yellow with age.

The paired fruits ripen to orange or red. They mature in July and can persist through the winter.

A rapid invader that leafs out early and forms dense thickets, it outcompetes native flora and fauna, displacing native shrubs, trees and herbaceous plants. Birds and mammals spread the seeds and the plant can also spread vegetatively.

Lonicera tatarica (Tatarian Honeysuckle)

A multistemmed deciduous shrub that can reach 10 feet tall. A native of Siberia and China, it was introduced to the U.S. in the 1750s as an ornamental.

Ovate bluish-green leaves are 1-2.5 inches long and half as wide.

Pink to red (sometimes white), lobed tubular flowers are borne in pairs in the leaf axils in May and June.

The quarter-inch berries turn orange/red in the fall and can persist through the winter.

It leafs out early and rapidly infests forests, fields, roadsides and floodplains, outcompeting native species in the process.

Lonicera x bella (Bell’s Honeysuckle)

Shrubs can reach 20 feet high and wide. The light green oval leaves are oppositely arranged. They’re 1-3 inches long and about half as wide.

The plant flowers in May and June from leaf axils. The paired flowers are typically pink but often yellow with age.

Red berries form in pairs and the seeds are dispersed by birds.

This is a hybrid of L. tatarica and L. morrowii.

Forms dense stands that displace native species.

Lonicera xylosteum (Dwarf or Fly Honeysuckle)

Introduced from Eurasia, it can now be found all over the northeastern U.S. Tolerant of poor soils, it can grow to 10 feet tall.

The deciduous elliptical leaves are arranged oppositely and 1-2.5 inches long.

Creamy white flowers appear in pairs at the axils of leaves in May.

The dark red berries, when eaten by birds, help increase its range.

– Will Rowlands

For more information visit the Connecticut Invasive Plant Working Group’s website at cipwg.uconn.edu

CONTROL

Begin control in late summer or early fall before seeds can be dispersed by birds or mammals. When populations are low, hand pulling of seedlings or young plants is an option. A weed wrench may prove helpful for larger plants. Just cutting the plant will encourage new growth.

The most effective control method is to prevent establishment by regularly monitoring for and removing individual plants. Mowing, cutting, girdling and burning can help prevent its spread, but will not kill the plant. Herbicide use in combination with controlled burning may be the most effective way to control large populations. Follow herbicide instructions carefully … the label is the law.