By Dr. Kelsey E. Fisher

Monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) are a charismatic species known for their characteristic orange and black coloration and annual migration from Mexico to Canada. Monarchs overwinter in Central Mexico huddled together in high elevation oyamel fir trees. Throughout the spring and summer months, monarchs undergo a multi-generational northern migration through the United States and into Canada.

[The lovely photo of an adult monarch on a purple coneflower was taken by Jacqueline Pohl from Iowa State University.]

During the summer breeding period, monarchs are widely distributed across the United States and Canada, where adult females lay eggs and caterpillars feed on their obligate host, milkweed (Asclepias spp.). In the fall, a single generation of adult monarchs travels south to their overwintering site, the nationally protected Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, in Mexico, where they cluster until the following spring.

The monarch butterfly holds a special place in the hearts of many because their historic large population size and wide distribution across the United States made them common during the summer months. People have memories of watching the caterpillars grow in science class as their teachers taught about metamorphosis and seeing monarch roosts form in their backyard during the southern migration in the fall.

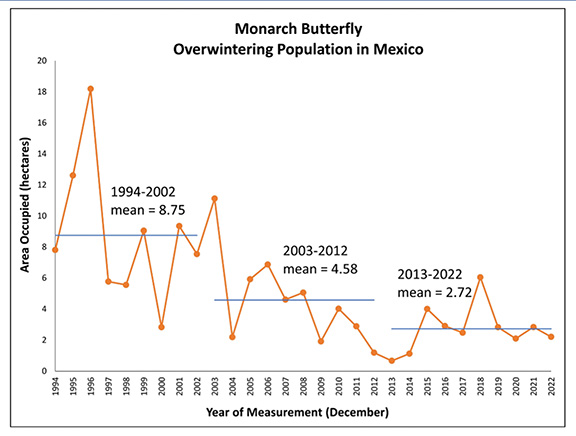

Unfortunately, the monarch butterfly is an example of a common species that is becoming less common because of human impact. Because monarchs overwinter in clusters, we’ve had a great

opportunity to monitor the population size annually. Each December, members of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve measure the amount of space the monarchs occupy in hectares as a proxy for population size. From these estimates, we have seen a significant population decline over the past 30 years (see figure below).

The monarch butterfly population decline is linked to many factors but is most significantly associated with the loss of habitat including milkweed and nectar resources because of land conversion, agriculture intensification, and urbanization.

As of 2017, the approximate 1.6 billion stems of milkweed in the monarch’s breeding range were able

to support approximately 3.2 hectares of overwintering monarchs in Mexico. To support a resilient population of six hectares of overwintering monarchs, an approximate 1.3 billion stems (3,070,027 hectares or 7,586,202 acres of pollinator habitat including milkweed) need to be established.

Knowing the enormity of this task, the midwestern states established a strategic plan to reach this goal by 2038. Even with a strategic plan, this huge undertaking requires “all hands on deck” across the monarch’s breeding range, including Connecticut. It is everyone’s responsibility to do what they can to help the monarch butterfly.

Before I moved to Connecticut in January 2023 for a job as an Assistant Scientist at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven, Connecticut, I lived in Iowa where I spent seven years collaborating with an interdisciplinary team of scientists at Iowa State University associated with the Iowa Monarch Conservation Consortium (see photo below).

With a final goal in place to establish 460,504 hectares of habitat in Iowa over 20 years, we came together to figure out where monarch habitat should be planted first so that it makes the biggest impact. Our goal was to determine how to maximize our efforts and establish milkweed in places where monarchs would find it and use it while we slowly make progress to reach the aimed acreage.

With finite resources, there were two approaches our team could have taken, (1) establish a few large (~20-hectare) patches of habitat including milkweed and nectar resources or (2) establish many small (1-2 acre) patches across the landscape.

Monarch females are highly mobile. When they find an area that contains milkweed, they lay a few eggs and then continue across the landscape in search of new milkweed patches – figuratively, they do not lay all their eggs in one basket. Because of this natural behavior, each female monarch will lay more eggs across her lifetime if milkweed is distributed in small patches rather than as a large field of milkweed.

Not only are small patches better for monarch butterfly behavior, but this approach also coincides with land utilization in the Midwest. Rather than taking profitable land out of corn and soybean production, we advocated to establish habitat on small, underutilized land, such as areas where the cost to maintain the land exceeded the potential profit, areas that are difficult to farm because they are on a slope or far away from the main farm, or areas that are currently being mowed. Therefore,

we devised a plan to collaborate with landowners to plant small pollinator plantings.

To better understand where small patches should be distributed across the landscape, I focused my research efforts on understanding monarch butterfly movement ecology. Rather than placing small patches in random locations, if we establish habitat in places that align with monarch’s natural movement behaviors, monarch females will be more efficient at finding milkweed.

This idea is called creating functional connectivity. I asked questions like: “After a monarch leaves a habitat patch, what flight patterns does it take while searching for the next patch;” “How close do patches need to be in order for monarchs to detect the presence of the next patch;” “How long does it take for monarchs to find the next habitat patch when it is various distances away from the current patch.”

Through a series of field studies, I gained empirical evidence to answer these questions. My approximations were fed into a spatially-explicit model to see how movement behaviors and habitat distribution across the county-scale influence egg accumulation. With a modelled, functionally connected landscape, monarchs can lay more eggs across their overall lifetime.

Our work in Iowa is applicable for monarch butterfly conservation across their breeding range. From my work specifically, I have one recommendation for Connecticut gardeners. Plant and maintain the monarchs’ obligate host plant, milkweed. Adult monarchs need milkweed to lay eggs and caterpillars need to feed on milkweed. You could plant any species of milkweed, but common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) will likely be the easiest to purchase commercially.

If you have the ability to select a location for habitat establishment, consider how your property is related to other pollinator gardens in your neighborhood and town. We recommend that establishing habitat within 50 meters of other pollinator habitat will create a functionally connected landscape for monarch butterflies.

Because selecting from multiple potential locations is a luxury, if your garden is not within 50 m of another habitat, it’s alright. Monarchs will eventually find your garden, and you are providing the one thing they really need, milkweed! But this provides an opportunity for you to convince your neighbors to establish milkweed and nectar plants. This will help create a functionally connected landscape for monarch butterflies that will increase the amount of time monarchs spend interacting with and laying eggs on milkweed and less time searching for their next oviposition site.

Kelsey E. Fisher is an Assistant Agricultural Scientist II in the Entomology Department at CAES. Kelsey earned her PhD in Entomology from Iowa State University, MS in Entomology from the University of Delaware, and BS in Biology from Widener University. Kelsey identifies as an insect movement ecologist as her research focuses on discerning animal movement patterns and space use in fragmented landscapes to understand movement and dispersal behavior of vagile insect species at various spatial scales. Kelsey employes multiple research methods in the field, greenhouse, and lab to address research questions related to management of pest insects and conservation of beneficial species, including radio telemetry, population genetics, stable isotope analysis, geospatial analyses, and spatial modeling. Most recently, Kelsey studied monarch butterfly movement in Midwest agroecosystems. Most notably, evidence from this work suggests milkweed and nectar resources be established within 50 meters of establish habitat to create a functionally connected landscape that facilitates monarch movement. Currently, Kelsey is building from her experience with monarchs to address research questions that provide management recommendations for other insects, including bumble bees and spotted lanternfly.